[Interview] Manga Artist Undertakes the Monumental Task of Adapting the "Greatest SF Novel of the 20th Century" into Manga: "I Want to Illustrate the Images in the Author's Mind"

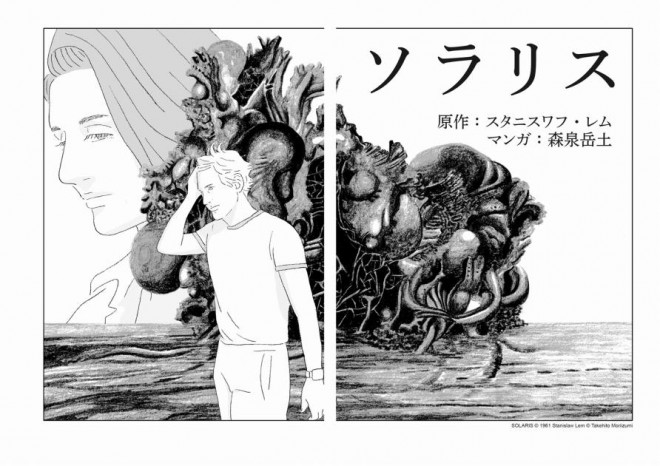

Sixty-three years after its first edition, the classic sci-fi masterpiece "Solaris" by Stanisław Lem has been adapted into a manga. The artist behind this ambitious project is Takehito Moriizumi, known for his unique art style and intricate narrative structures that create a one-of-a-kind world. Amidst various opinions about media adaptations of classic works in recent years, Moriizumi has taken on the challenge of bringing this beloved 20th-century sci-fi work to life. We spoke with him about his approach to this adaptation and the significance of adapting a literary masterpiece into manga.

Manga Artist Takehito Moriizumi

"Staying True to the Original Doesn't Mean Reproducing Every Word"

—The manga serialization of "Solaris" began in July on Hayakawa Publishing's newly launched digital comic site, "Hayakomi." I understand that this manga adaptation was your own suggestion, Mr. Moriizumi.

"I first read Lem's 'Solaris' in my twenties. I vividly remember the shock of realizing 'This is what sci-fi can do!' It was an unforgettable experience, like nothing I had ever encountered before. 'Solaris' is a story about contact with something other than humans, a love story, and a gothic horror where something alien appears in a confined space. It’s a piece of false history, a parody, and a work rich with the scent of literature, blending various genres."

—You fell in love with the story and decided to adapt it into manga.

"Yes, exactly. Moreover, 'Solaris' has a certain 'space' that I can immerse myself into. It’s what I meant when I mentioned the 'scent of literature' earlier—when choosing a work to adapt into manga, whether it has such space is one of my key criteria. By 'space,' I don’t mean adding episodes or altering the story but rather having the room to express the story through drawings and manga. So, when I re-read the novel, I thought, 'I can definitely illustrate this,' and told the editor I could draw 'Solaris.' The editor seemed surprised, 'Solaris? Really?' [laughs]"

—When it comes to adapting a masterpiece, fans of the original often expect a "faithful reproduction." How did you approach this manga adaptation?

"I read the original thoroughly and recreated it with remarkable fidelity [laughs]. But I don’t believe that being faithful to the original means reproducing every single word. Novels have their own advantages, and manga has its own. What I mean by 'staying true to the original' is not simply converting the novel's text into manga but deciphering the vision that Lem must have had in his mind before writing the novel and then transferring that vision into the manga medium. It’s like imagining how Stanisław Lem would have depicted Solaris if he had created it as a manga instead of a novel."

—You illustrated the images in the author's mind.

"Yes, exactly. I aimed to faithfully recreate the future image that Lem must have envisioned and to express the atmosphere and world of the original work. For instance, in the space station where the protagonist is, the recording devices use cassette tapes. If I replaced them with IC recorders or depicted computer monitors as thin LCD screens instead of CRTs, that wouldn’t be Lem’s vision anymore. It would be like revising the history of Solaris.

Therefore, I believe that depicting it with the level of technology described in the novel shows respect for the original. For example, while computers appear in the novel, the word 'search' never does. That is the sense of the future in Solaris, and we shouldn’t overwrite the future that didn’t come to pass with current technology or values."

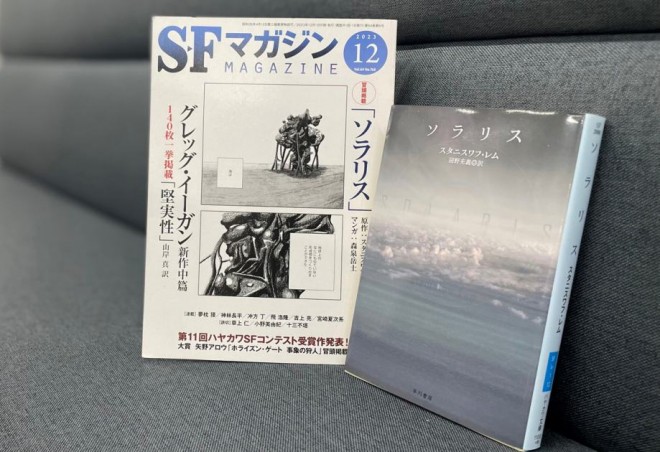

SF Magazine by Hayakawa shobo

The “Ocean with Intelligence” Where No Right Answer Exists: "It Was Hard to Know How to Interpret and Draw It"

—Manga artist Yukari Takinami praised your work on X (formerly Twitter), saying, "The space station and equipment depicted, such as tape recorders, are true to what was imagined when the novel was written, and this is the essence of near-future classic comic adaptation!" Could you tell us more about how you expressed the atmosphere and world of the original work?

"Despite the dense descriptions in the original work, there’s this strange space for the reader’s imagination to enter. Maybe it’s because much of what is depicted, aside from the sea and historical elements, is the protagonist's 'thoughts' rather than actions. This gives the work a 'white' impression for me. So, I wanted to depict the interior of the station with a somewhat white atmosphere and world.

On the technical side, one approach I took in this work was to have only one person speaking in a single panel. This was also a way to create space. If you cram two or three lines of dialogue into a single panel, it becomes noisy. Occasionally, I draw panels with two people talking to create a rhythm and avoid monotony, but I structure the manga with spacious panels to allow readers to feel the same atmosphere that the original work evokes."

—Which part of the depiction did you focus on the most?

"It has to be the sea! What I had in my mind didn’t match the original when I re-read it, so I had to test my understanding. In contrast to the white atmosphere of the station, the sea is depicted with a blackish image. It’s mysterious, eerie, and impossible to comprehend at first glance. I wanted to convey that contact with humans would be difficult, that these were two worlds that would never mix."

—The "Ocean with Intelligence" covering the surface of the planet Solaris is described in the original as something that "could create formations unlike anything on Earth."

"Yes, how to depict these never-seen formations. Honestly, before I started drawing, I thought it would be tough, but as I worked on it, I found it increasingly enjoyable. I wanted to go the extra mile with the depiction, and the number of pages increased. I kept drawing this black sea, transforming into unrecognizable shapes page after page. My right arm became so stiff from the work that the chiropractor asked, 'What on earth have you been doing to get like this?' I was possessed by the need to draw the sea as accurately as possible [laughs]."

Manga Artist Takehito Moriizumi

A Fantasy World with No Right Answers: The Unique Challenge and Fun of Adapting SF

—Creating a world where no right answers exist is both the challenge and the charm unique to adapting SF novels. SF is often considered "difficult," but I think your version of "Solaris" is quite accessible.

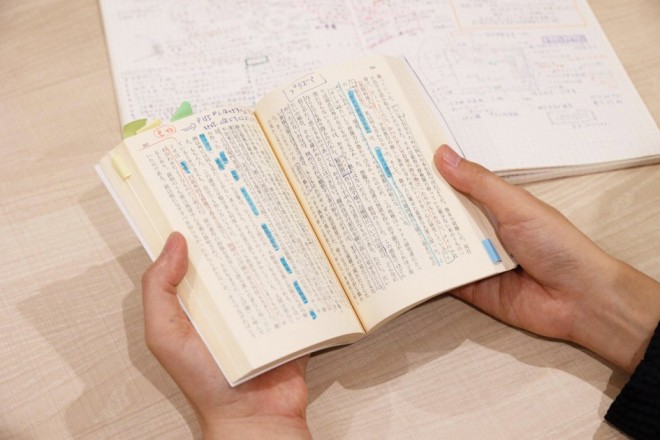

"When adapting into manga, the overall structure is crucial for readability. I started by picking out the necessary texts and information from the original, organizing them in a notebook. The original contains so much information that it’s compelling as a novel, but it might confuse readers if directly translated into manga. So, I picked out the key points, trimmed the excess, but never cut the essential core. For instance, where the confusion and incomprehensibility are part of the charm, I ensured that the presentation still made that part of the appeal clear. In this way, I structured the manga to convey the essence of the original effectively."

Moriizumi’s personal copy of "Solaris," filled with notes and the notebook used to plan the adaptation.

"Capturing the Essence of the Original Is Key" in Media Mix Adaptations

—I sense a deep "love for the original" in your work. These days, there are cases where issues arise in media mix adaptations due to deviations from the original...

"When adapting novels or manga into films, many people are involved in the production process, making consensus-building extremely difficult. That’s why it’s hard to say that there’s one correct way to do media mix adaptations—it really depends on the case. However, if I were to speak generally, I would say that even if the work is an adaptation, it should be considered the film director’s work. For example, my father-in-law, the film director Nobuhiko Obayashi, made significant changes to the originals in films like 'The Little Girl Who Conquered Time' and 'The Reason,' but the original authors were thrilled with the final films. This was largely due to the director's skill, but I believe it’s also crucial that the essence of the original was captured when adapting it into film."

—Being faithful to the original isn’t the only correct approach, then.

"For example, even if a scene from the original is omitted or a new scene is added, as long as the essence and world of the original work are preserved, it can still be accepted. Novels have their advantages, manga has its advantages, and films have their advantages. I’ve heard that some media mix adaptations are driven by marketing strategies, like 'This project will be successful because this original work is currently popular,' but as long as the creators have the understanding to capture the essence of the original, respect for the work, and the ability to bring it all together—these three elements are crucial—I think the adaptation won’t stray too far, no matter the reason behind its production. However, as I mentioned before, it’s case by case, so it’s not that everything else is wrong. Plus, there’s the consideration of the fans' feelings. And even among fans, there’s no single opinion."

Manga Solaris

Manga Adaptations of Classic Novels Are Essential to Keep These Works Alive

—Some argue that manga adaptations of classic novels are essential to keep these works alive and appeal to a broader audience. What do you see as the role of manga adaptations?

"Of course, I’d be delighted if people who read my adaptation of 'Solaris' go on to read the original novel, but I leave that to the editors. My focus is on sincerely adapting the novel into manga. If it becomes a good work, it will naturally attract more readers—that’s how I see it, though it may sound optimistic. Honestly, I’m so immersed in the joy of drawing 'Solaris' that I haven’t had much time to think about the 'role of manga adaptations' [laughs]. It feels like having a mental dialogue with Lem about 'Solaris' while working on it. Like, 'Is this what you meant?' 'Yes, exactly,' 'I see, I get it.' That kind of imaginary 'conversation' is an irreplaceable joy."

Manga Artist Takehito Moriizumi

—Your manga adaptations are widely supported because of your consideration for the original work and your respect for the author. Since the serialization began, people on X (formerly Twitter) have praised your work, saying, "I wasn’t sure what to expect, but the art is amazing..." "Moriizumi’s technique is perfect for depicting the ocean of Solaris..." and "Wow! This space is fantastic!"

"I’m sincerely engaging with the original, so it’s gratifying to receive such praise. There were comments on 'X' saying that they had given up on reading the novel because it was too difficult, but they wanted to try reading the manga. I hope to bring this manga adaptation of 'Solaris' to those who haven’t read the original, and I’m confident they’ll have a similar experience to reading the novel."

(Interview and Text by Go Fukuzaki; Photography by Tohru Tokunaga)

Source : ORICON NEWS

![[INTERVIEW] Pete Docter of Pixar Discusses Anxiety Over Ennui and the Joy of Global Success](/upimg/thumb/1000/1344/img280/e9b03b950f67b3052f33628b7be6e33d.jpg)